Private arbitration or (dispute) adjudication is a process built on consent in that parties agree that their respective disputes shall be settled by arbitrators or arbitral panels. Usually such procedures are embedded in domestic law. The powers and authorities of arbitrators rest upon arbitration law subject to an agreement by the parties.

Arbitral tribunals have considered that arbitration is an entirely alternative procedure in regard to which the parties are their own legislators in the contracts which they make (see ICC Award No 4620, Interim Award dated April 18, 1984 quoted from Redfern, Law and Practise of International Commercial Arbitration, 4th edition, London 2004, 180).

The courts usually agree with the above view. In relation to dispute adjudication and arbitration reference can be made to the following passage from the speech of Lord Mustill in the House of Lords in Channel Tunnel Group v. Balfour Beatty [1993] AC 334 at 353 in relation to a choice made by the parties as to how disputes should be dealt with:

“Having made this choice I believe that it is in accordance not only with the presumption exemplified in the English cases cited above that those who make agreements for the resolution of disputes must show good reasons for departing from them, but also with the interests of the orderly regulation of international commerce that, having promised to take their complaints to the experts and if necessary to the arbitrators, that is where the appellant should go. The fact that the appellants now find their chosen method too slow to suit their purpose is, to my way of thinking, quite beside the point.“

Moreover in Qantas Airways Ltd. v. Dillingham Corp., [1985] 4 ‘SWLR 113, 118 it has been held:

“It is now more fully appreciated than used to be the case that arbitration is an important and useful tool in dispute resolution. The former judicial hostility to arbitration needs to be discarded and a hospitable climate for arbitral resolution of disputes created. It used to be thought that difficult questions of law or complex questions of fact presented a sufficient reason for relieving a party from the obligation to abide by an arbitration clause. That approach should be treated now as a relict of the past. The courts should be astute in ensuring that, where parties have agreed to submit their disputes to arbitration, they should be held to their bargain even if this may involve additional expense and cost”.

Whatever the parties agree on may be subject to interpretation by arbitrators. In this context the word “interpretation” should not only be understood literally. Rather arbitrators are likely to implement (frequently unconsciously and not at all in bad faith) their proper understanding of arbitration. Their cultural and legal imprints and related fundamental understanding of how to proceed and to apply the contract and the law may have a strong impact on the expected outcomes.

FIDIC Dispute Resolution

FIDIC (the International Federation of Consulting Engineers) suggests that the parties to a construction contract should agree on the following:

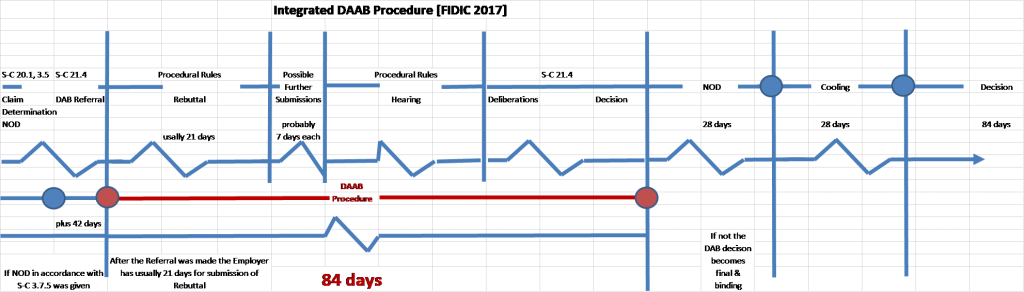

If a Dispute arises out of or in connection with the Contract the parties may refer the dispute to the DAB or DAAB. Within 84 days after receiving such reference, or within such other period as may be proposed by the DAB or DAAB and approved by both Parties, the DAB or DAAB shall give its decision, which shall be reasoned and shall state that it is given under this Sub-Clause. The decision shall be binding on both Parties, who shall promptly give effect to it unless and until it shall be revised in an amicable settlement or an arbitral award as described below. Unless the Contract has already been abandoned, repudiated or terminated, the Contractor shall continue to proceed with the Works in accordance with the Contract.

If either Party is dissatisfied with the DAB’s or DAAB´s decision, then either Party may, within 28 days after receiving the decision, give notice to the other Party of its dissatisfaction (NOD). If the DAB or DAAB fails to give its decision within the period of 84 days (or otherwise approved) after receiving such reference, then either Party may, within 28 days after this period has expired, give notice to the other Party of its dissatisfaction.

In either event, this notice of dissatisfaction shall state that it is given under this Sub-Clause, and shall set out the matter in dispute and the reason(s) for dissatisfaction. Except as stated in Sub-Clause 20.7 [Failure to Comply with Dispute Adjudication Board’s Decision] and Sub-Clause 20.8 [Expiry of Dispute Adjudication Board’s Appointment] neither Party shall be entitled to commence arbitration of a dispute unless a notice of dissatisfaction has been given in accordance with this Sub-Clause. Regarding FIDIC 2017 Sub-Clauses 21.7 and 21.8 refer.

If the DAB or DAAB has given its decision as to a matter in dispute to both Parties, and no notice of dissatisfaction has been given by either Party within 28 days after it received the DAB’s or DAAB´s decision, then the decision shall become final and binding upon both Parties. It may then become enforced under Sub-Clause 20.7 FIDIC 1999 or Sub-Clause 21.7 FIDIC 2017.

If the DAB or DAAB has given its decision as to a matter in dispute to both Parties, and a notice of dissatisfaction has been given by either Party within 28 days after it received the DAB’s or DAAB´s decision, then the decision is subject to further review and not yet final and binding upon both Parties but only (temporarily) binding (unless and until revided in arbitration).

It cannot be overestimated that FIDIC forms of contract encourage the parties and the DAB/DAAB to settle upcoming disputes amicably. The 2nd Edition (2017) includes even a defintion of “Informal Assistance”. Such informal assistance is available on various occasions. However, the parties frequently do need a bit of time before they make use of dispute avoidance options because the use of such a feature requires mutual trust in the total independency and neutrality of the DAB, making use of its authority to provide Informal Assistance in fair and balanced manner and also in an appropriate manner, because the aim should always be to attain good workmanship and fitness for purpose within time and budget, if possible. In any case the express authority to provide informal assistance makes the DAB a unqiue feature which shall not be confused with any type of arbitration or mere expert (witness) statements.

ICC Arbitration Rules (1998 et seq.)

Under FIDIC forms of Contract the referral of disputes to arbitration is (or should be) the last resort. If arbitration is considered to be unavoidable arbitration cases must be filed to the ICC Court and the ICC Arbitration Rules shall apply; exceptionally the FIDIC Green Book, 1st edition referred to UNCITRAL Rules. FIDIC does not specify or determine whether for instance the Arbitration Rules 1998, 2012, 2017, or 2021 apply. Hence FIDIC refers to an unpredictable or floating set of Rules which is subject to changes made by the ICC, which apply depending on the date the referral was made.

On 4 November 2016, the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC) has launched a revised set of its previous Arbitration Rules (the “2012 ICC Rules”). Subsequent revisons have followed.

The revised arbitration rules (hereinafter the “Revised ICC Rules”) are aimed at improving the efficiency and transparency of ICC arbitration. They came into force on 1 March 2017. From then on these revised rules were applicable to all proceedings that commenced after that date, irrespective of the date of the arbitration agreement or when the contract containing the arbitration clause in question was concluded. In addition, the parties are free to agree that the Revised ICC Rules shall apply to arbitration proceedings having commenced before 1 March 2017.

Further revised ICC Rules of Arbitration have entered into force on 1 January 2021, which define and regulate the management of cases received by the International Court of Arbitration from 1 January 2021 on.

The ICC Rules of Arbitration offer

- a regular procedure (the Arbitration Rules), and

- an emergency arbitration procedure (Appendix V to the Arbitration Rules)

- an expedited procedure providing for a streamlined arbitration with reduced scales of fees (Appendix VI to the Arbitration Rules).

Regular Arbitration

Regarding regular arbitration the following details are noteworthy:

- Unlike other arbtration rules the ICC Arbitration Rules require the parties to sign the Terms of Reference (Art. 23 Arbitrration Rules 2021)

- The time limit for transmission of the Terms of Reference to the Court is equal to 30 days after the date on which the file has been transmitted to the tribunal] [Article 23(2)];

- Article 6(3) is not limited to just the party against which a claim is made. The language provides that if any party raises one or more pleas concerning the existence, validity or scope of the arbitration agreement, the arbitration will still continue.

- Nothing prevents the ICC from communicating reasons for decisions on appointment, confirmation, challenge, or replacement of arbitrators; the contradicting part of Article 11(4) has been deleted; [a]ny party will now be in a position to ask the ICC Court to provide reasons for its decisions.

- The scale of administrative fees to be paid to the ICC, reflects also the expedited proceedings: the flat fee for claims exceeding US$ 500 million has risen from US$ 113,215 to US$ 150,000 in Appendix III Article 3(2).

Expedited Arbitration

Art. 30 ICC Rules and Appendix VI provide for an “expedited arbitration procedure (the “Expedited Procedure”) for “smaller” claims. The Expedited Procedure shall apply to disputes if

- a) the amount in dispute does not exceed the limit set out in Article 1(2) of Appendix VI at the time of the communication referred to in Article 1(3) of that Appendix; or

- b) the parties so agree.

The aformentioned maximum amounts are equal to:

a) US$ 2,000,000 if the arbitration agreement under the Rules was concluded on or after 1 March 2017 and before 1 January 2021 or

b) US$ 3,000,000 if the arbitration agreement under the Rules was concluded on or after 1 January 2021.

Whether the Expedited Procedure for “smaller claims” is fit with FIDIC and the needs under FIDIC may require further attention. Tough the Court may, upon the request of a party before the constitution of the arbitral tribunal or on its own motion, determine that it is inappropriate in the circumstances to apply the Expedited Procedure Provisions. But this may require a sound understanding of the context in which claims have been made and brought to the DAB and arbitration. For instance EOT claims may as such not have a significant value; but years later the consequences of failure to obtain EOT may be significant subject to a claim on delay damages. The FIDIC wording may require prompt decisions but not rough decisions. A detailed investigation of pros and cons might become necessary. Also the reduced time for the preparation of Terms of Reference may not always be in appropriate for complex construction litigation. Time will show to which extent ICC arbitration is still suitable for all type of disputes. While FIDIC promotes (for good reasons) rapid (DAB) procedures at first instance the same might not always be true for subsequent arbitration where special needs of the construction business may require solutions where speed should not be the most prominent aim.

Enforcement of Arbitration Decisions

Arbitration awards made orders of court may be enforced in the same manner as any judgment or order to the same effect, including execution by state mechanisms. In international cases the 1958 New York Convention on the recognition and enforcement of arbitral awards will be a useful tool if the defendant does not comply with the award.

Challenge of DAB Members

The ICC has introduced a new feature in cooperation with FIDIC. The FIDIC Appendix III Challenge of DAAB Member(s) under the 2017 FIDIC Contracts to the ICC Dispute Board Rules includes the provisions with are needed in accordance with Rules 10 and 11 of the FIDIC Proecedural Rules (FIDIC 2017).

The procedure will not apply to FIDIC 1999 unless agreed otherwise in express terms. The 2nd Edition of the FDIC Rainbow includes special provisions in the Procedural Rules 10 and 11.

FIDIC Arbitration

Under FIDIC 1999 any dispute upon which a final and binding DAB decision does not yet exist can be referred to arbitration under Sub-Clause 20.6.

The relevant FIDIC (1999) clauses read as follows:

[FIDIC 1999] 20.6 Arbitration

Unless settled amicably, any dispute in respect of which the DAB’s decision (if any) has not become final and binding shall be finally settled by international arbitration. Unless otherwise agreed by both Parties:

(a) the dispute shall be finally settled under the Rules of Arbitration of the International Chamber of Commerce.

(b) the dispute shall be settled by three arbitrators appointed in accordance with these Rules, and

(c) the arbitration shall be conducted in the language for communications defined in Sub-Clause 1.4 [Law and Language].

The arbitrator(s) shall have full power to open up, review and revise any certificate, determination, instruction, opinion or valuation of the Engineer, and any decision of the DAB, relevant to the dispute.

…

The ICC Rules as referred to in FIDIC are widely used throughout the world. In 2016 roughly 950 new cases were filed under the ICC Rules.

Note that MDB harmonised version 2010 of the FIDIC Red Book currently refers to UNCITRAL arbitration rules. THe 2nd edition of the Green Book has abondoned the reference to UNCITRAL arbitration rules.

[FIDIC 1999] 20.7 Failure to Comply with Dispute Adjudication Board’s Decision

In the event that:

(a) neither Party has given notice of dissatisfaction within the period stated in Sub-Clause 20.4 [Obtaining Dispute Adjudication Board’s Decision],

(b) the DAB’s related decision (if any) has become final and binding, and

(c) a Party fails to comply with this decision, then the other Party may, without prejudice to any other rights it may have, refer the failure itself to arbitration under Sub-Clause 20.6 [Arbitration], Sub-Clause 20.4 [Obtaining Dispute Adjudication Board’s Decision] and Sub-Clause 20.5 [Amicable Settlement] shall not apply to this reference.

Hence under FIDIC the parties make specific agreements for the resolution of disputes which may arise out of or in connection with the contract. The parties must show good reasons for departing from them. Unless they can show good reasons shall simply follow the agreed procedural steps like a road map. The Swiss Supreme Court (Bundesgericht (German)-Tribunal federal (French)-Tribunale federale (Italian)) has held on 7 July 2014 (file number 4A_124/2014) that the relevant FIDIC wording establishes a valid and enforceable arbitration clause.

However, the 1999 FIDIC set of provisions in relation to dispute adjudication and arbitration do not always cover all issues which may come up. It is worthwhile to note that inter alia the following aspects should be taken in consideration:

- Reference to procedural rules is common practise. Under FIDIC forms of contract usually ICC rules apply. However, under the MDB harmonised version (2010) the Contract refers to UNCITRAL rules. UNCITRAL does not operate as a nominating entity in case of failure to agree on the members of the arbitral panel. Rather UNCITRAL provides on how to appoint a nominating body.

- It is not intended to conduct the proceedings in more than one language. Sub-Clause 20.6 FIDIC (1999) provides that the proceedings shall be conducted in the language which has been indicated in the Appendix to Tender (or Contract Data, as the case may be) being the Communication Language. Though it is principally possible to conduct dispute adjducation or arbitral proceedings in more than one language this may lead into much debate and additional dispute.

- In England, the Limitation Act 1980 does not apply to expert determination and dispute adjudication since the Act would only apply to the limitation period in relation to any court proceedings. Hence the Parties to a contract must take appropriate steps in order to ensure that the time bar defence under any limitation rules will be avoided.

- Insolvency cases may cause problems to the extent that they may require a claimant to introduce court actions for the registry of claims. The question then arises whether such requirement will be met if a dispute will be referred to a DAB or the arbitral tribunal. If the insolvency laws provide time bars for taking such action it must be ensured that the appropriate steps will be taken in a timely manner.

- Merely binding DAB decisions can be enforced in arbitration through interim awards

- Any final arbitral award will fall under Sub-Clauses 14.3 and 14.6 FIDIC (1999) requiring the claimant to apply for a Payment Certificate in order to become entitled to payment.

The 2nd edition 2017 of the FIDIC Rainbow has shifted the arbitration wording to Clause 21, without major substantial changes. Are noteworthy the following minor or unsurprising changes:

- reference to binding and final and binding DAB decisions in Sub-Clause 21.7 (basically in line with the Memorandum April 2013 and the FIDIC Gold Book)

- reduction of the cooling down period to 28 days under Sub-Clause 21.5

- awarded payments become due without further certification in accordance with Sub-Clause 21.6 last para.

Dr. Götz-Sebastian Hök is a FIDIC listed (FCL certified since 2021) dispute adjudicator (President´s List) and practising arbitrator and acts as a counsel in major arbitrations. He has experience under both, ICC and UNCITRAL arbitration rules. He was one of the speakers on the ICC FIDIC Conference in Sao Paulo in June 2011 and he was one of speakers of the DRBF conference in Singapore in May 2014 and Berlin 2018. Dr. Götz-Sebastian Hök is the legal advisor of the FIDIC Task Groups TG 9 (Design and Build Subcontract) and TG 11 (Operate, Design and Build). He has acted as an expert witness in court and arbitration hearings worldwide. From 2016 onwards he was a member of the expert commission for the review of the DIS Arbitration Rules.

The author has published various papers and articles on the subject matter, e.g.

Sebastian Hök, Der Persero Fall: Zur Vollziehung lediglich bindender DAB Sprüche nach FIDIC (1999), [2016] ZfBR 211 (in English: The Persero Case: On the enforcement of merely binding DAB Awards in accordance with FIDIC (1999), …

Sebastian Hök, Zur Bindungswirkung von DAB Entscheidungen nach FIDIC – Anmerkung zur Entscheidung des Court of Appeal Singapore, Urteil vom 13.7.2011, 59/2010 CRW Joint Operation v. PT Perusahaan Gas Negara, [2012] ZfBR 107 et seq. (in English: On the binding effect of DAB decisions under FIDIC – explanatory notes on the decision of Court of Appeal of Singapore in CRW Joint Operation v. PT Perusahaan Gas Negara, decision dated 13 July 2011, 59/2010 …)

Sebastian Hök, FIDIC Memorandum 2013 zur Vollziehung von vorläufig bindenden DAB Sprüchen mit einem Blick auf die DIS Schiedsgutachterordnung [2013] ZfBR 419 et seq. (in English: FIDIC Memorandum on the enforcement of provisionally binding DAB decisions with a view to the [German] DIS Expert Determination Rules …)

Sebastian Hök has also contributed to the JICA DB Manual.

Oldenburgallee 61

14052 Berlin

Tel.: 00 49 (0) 30 3000 760-0

Fax: 00 49 (0) 30 51303819

e-mail: ed.ke1745648151oh-rd1745648151@ielz1745648151nak1745648151

https://www.dr-hoek.com